Excel Never Dies - Not Boring by Packy McCormick

Welcome to the 1,370 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since last Monday! 🤯 If you aren’t subscribed, join 37,892 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

This week’s Not Boring is brought to you by … Michael Bolton

(Okay, not actually Michael Bolton. But he does star in this sponsor’s latest ad campaign, so ... close enough.)

I’ve talked (and written) about Public.com before, so you know the deal. One part investing app, one part community where you can discuss business trends and companies you believe in.

Some of you might be looking for a new brokerage these days, so you should know that Public is making the process of transferring your portfolio over ridiculously easy. They’re even covering the transfer fees from your old brokerage.

For this week only, download the app with my link and you’ll start with $20 in free stock.

You can even follow me and Michael Bolton there (@packym and @michaelbolton, respectively). Our music video drops soon 🔥

- The fine print: This offer is valid for U.S. residents 18+ and is subject to account approval. Free stock offer valid for new accounts only. See Public.com/disclosures/

Hi friends 👋 ,

Happy Monday!

One of the places I learn the most is a group chat I have with my friends Dror Poleg and Ben Rollert. Dror, who writes about the history and future of work, cities, and finance, and Ben, who is the founder and CEO of Composer, are two of the smartest people I know.

Ben, the most technical of the trio (followed by Dror, then me), also happens to be an excellent writer. In late February, he released The Composer Manifesto, to make the case for investing as a creative endeavor. It’s tailor made for the two types of people who read Not Boring -- investors and tech people -- and you should read it:

So when Ben texted us about how underrated Excel’s power is, I asked him to write about it with me. He opened my eyes to so much depth I didn’t know existed in the product in which I spent every waking hour for the formative years of my career. We’ll try to do the same for you.

Let’s get to it.

In the popular marketing book Alchemy, Rory Sutherland writes, “A spreadsheet leaves no room for miracles.” We could not disagree more strongly.

Most software we use at work exists in one of two categories:

- It’s new and we love it for now.

- It’s old but we have to use it and we hate it.

But there’s one software product born in 1985, before many of us were even a twinkle in our parents’ eye, that inhabits its own category: it’s old, but we love it, we always will, and you’ll have to pry it from our cold, dead, fingers. That product, of course, is Microsoft Excel.

Anyone who has worked in finance or consulting grew up on it, learned to love it over thousands of hours of practice and improvement. Whether they realized it or not, they were becoming programmers, or at least no-code practitioners before the no-code movement took off. “Proficient in the Microsoft Office Suite” is so meaningless that it’s become a meme, but the ability to bend one specific Office program, Excel, to one’s will is a badge of honor.

But the enduring, passionate user fervor for the product isn’t even its most unique attribute. Excel’s most lasting impact extends beyond the spreadsheet itself.

Excel may be the most influential software ever built. It is a canonical example of Steve Job’s bicycle of the mind, endowing its users with computational superpowers normally reserved for professional software engineers. Armed with those superpowers, users can create fully functional software programs in the form of a humble spreadsheet to solve problems in a seemingly limitless number of domains. These programs often serve as high-fidelity prototypes of domain specific applications just begging to be brought to market in a more polished form.

If you want to see the future of B2B software, look at what Excel users are hacking together in spreadsheets today. Excel’s success has inspired the creation of software whose combined enterprise value dwarfs that of Excel alone. There are two main ways Excel has set the broad roadmap for the B2B software industry for decades, and will continue to for years to come:

- The Unbundling of Excel. Hundreds of B2B startups have been built by taking a job currently being done in Excel and trying to accomplish the job in more optimized, purpose-built B2B software. Every time you hear an entrepreneur say, “We’re replacing siloed spreadsheets and outdated processes with purpose-built software,” you’re hearing the Unbundling of Excel in real time. Many popular SaaS applications fall in this category. And yet, despite being “unbundled,” Excel keeps getting stronger.

- Inspired by Excel. That resiliency has inspired entrepreneurs to look more deeply at what makes Excel tick, and why. Adventurous builders are creating new software that doesn’t unbundle Excel, but is Inspired by Excel. Excel’s balance of usability and flexibility can be found in popular no-code and low-code products created over three decades since Excel first graced the screen. This source of inspiration is less direct and more meta; it is less about recreating anything concrete that happens in Excel, and more about capturing the essence of what makes Excel so successful.

We love Excel, everyone reading this probably loves Excel, and still, its impact is deeply underappreciated. Today, we’re going to fully appreciate it by covering:

- The History of Excel

- Excel as a Language

- The Lindy Effect

- Excel’s Limitations

- No-Code and the Unbundling of Excel

- Why Excel Will Never Die

A little competition isn’t new to Excel. It was born fighting.

We have Steve Jobs to thank for Microsoft Excel, and Microsoft Excel to thank for Apple. Spreadsheet software was the first truly killer app for the Mac and home PC, and the Mac’s graphical interface helped bring spreadsheets to the masses. The two propelled each others’ growth.

Excel wasn’t the first digital spreadsheet. When HBS student Dan Bricklin had to decide between doing spreadsheets for a case study by hand or on the school’s mainframe, he, like so many entrepreneurs, realized there had to be a better way. He launched VisiCalc, a “visible calculator,” in 1978. Computer Associates followed two years later in 1980 with SuperCalc. That same year, Mitch Kapor sold VisiPlot/VisiTrend to VisiCalc’s parent company, Personal Software, for $1 million, and joined to work as a product manager on VisiCalc.

In 1982, Kapor left to build a yet-to-be-named product that combined the spreadsheet with graphing, and somehow convinced Personal Software to carve the product out of his non-compete. “I am not sure why they agreed to this,” he wrote in an email, “Perhaps they felt I lacked credibility to pull off something this ambitious. If so, they underestimated me.”

Kapor founded Lotus in 1982 and launched 1-2-3 in 1983. In its first year of operations, Lotus did $53 million in revenue and IPO’d. The next year, it tripled revenue to $156 million. SaaS has replaced discrete sales as the go-to business model for software because it’s better for the customer, generates recurring revenue, and can lead to a higher Lifetime Value, but no SaaS company has ever put up such big numbers as quickly as Lotus did.

The same year Kapor founded Lotus, Bill Gates and the Microsoft gang released its first spreadsheet software: Multiplan. It was notable for using R1C1 addressing (row then column) instead of A1 (the column then row we’re used to), for aiming to be the most portable spreadsheet application, runnable on over 50 different computers, and not for much else.

Lotus 1-2-3 crushed Multiplan, and Microsoft went back to the drawing board with “Project Odyssey.” They originally built Odyssey to be a better spreadsheet than Lotus 1-2-3 on the PC, but two critical things happened during development that would catapult the project into a lead that it still holds today, 36 years later.

First, was the team’s motto: “Recalc or die.” According to Jeff Raikes, Mutiplan’s product manager and the man behind Office, “A brilliant programmer named Doug Klunder figured out how to do the calculation algorithm in two dimensions simultaneously so that we could recalculate even faster than Lotus 1-2-3.” Klunder’s innovation meant that instead of having to recalculate (recalc) every cell every time a cell changed, Odyssey only recalculated the affected cells. That gave it a huge speed and performance advantage over 1-2-3, which created the magical experience that any Excel user is familiar with: change an input, and watch worksheets full of outputs respond immediately.

Second, Gates and Raikes decided that they needed to take advantage of the graphical interface, so they switched mid-project from building for the PC, which was operated via command line interface, to building exclusively for Mac.

Jon Devaan, who worked on Odyssey, credited Jobs’ machine’s broad usability: “That was really the important thing at the time, to bring software from PhD thesis mode into something that an average person could use.”

Microsoft Excel 1 for Mac (1985), Source: Version Museum

With those two innovations, Microsoft launched Excel in 1985 exclusively on the Macintosh. It was that counterintuitive decision to launch on its competitor’s computer while Lotus 1-2-3 was stuck on its own MS-DOS, that brought Excel into the mainstream.

If you want to go really deep on the history of Excel, watch this whole video:

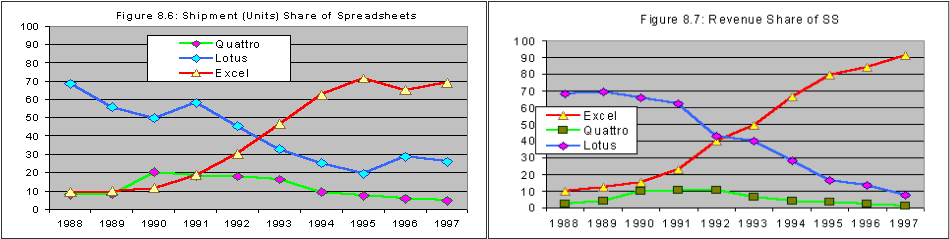

Excel quickly became the most popular spreadsheet program on the Mac, and then the most popular on Microsoft’s first GUI OS, Windows. It rode Windows’ growth to become the world’s most popular spreadsheet software by revenue (in 1991) and units shipped (in 1992).

Source: UT Dallas

It hasn’t looked back. While it’s difficult to break out spreadsheet market share today since Excel comes bundled with Office and Google’s Sheets comes with GSuite, Excel holds a dominant position (~80%+) by most estimates, with a near monopoly for more intensive use cases like financial modeling.

After 36 years, it’s hard to imagine a world without Excel. It’s likely the single application that would cause the most damage if it were wiped off the face of the earth tomorrow. Many of the world’s largest companies and financial institutions rely on Excel models to run their businesses, and today, Excel isn’t just a spreadsheet software; it’s a language.

Excel is the most popular programming language on earth, and most people who program in Excel don’t even realize they are, in fact, programming. There are an estimated 1.2 billion people who use Microsoft Office, and while it’s hard to know exactly how many people use Excel regularly, estimates put it at 750 million users. By comparison, as of 2018, there were only 10.7 million Javascript developers and 7 million Python developers.

Python and Javascript, the two most popular programming languages after Excel, are both Turing complete; that is, they can be used to perform any computation (in very simplified terms). Excel, on the other hand, was not Turing complete until very recently. In practical terms, this means that Excel simply could not be used as a substitute for a “true” programming language for many types of computational problems, no matter how clever the hacks a power user might think of.

(Note: VBA allows more technical people to build even more programs and automations, but we’re focused on what Excel can do for less technical users.)

Even if Excel is not as powerful as the languages professional developers use, and even if most of its users do not consider themselves programmers by trade, it’s hard to argue that working in Excel isn’t programming. When you layout formulas in cells in Excel, you are working with a kind of functional language. Excel is functional in that its formulas (or functions) generate the same exact output, given the same input, no matter what else is happening in your spreadsheet or workbook. You can also chain functions, passing the output of one function as the input to another, allowing for an enormous number of potential computational pipelines. Each time Excel adds a function, the power and flexibility of Excel is multiplied, since that new function can be chained to a large number of existing functions.

So if working in Excel is programming, why is it so much more accessible than other languages?

Declarative

Excel is declarative in that you define what you want by typing a formula, without having to worry about how to perform the step-by-step computations. I can calculate the Internal Rate of Return (IRR) on an investment without needing to know the formula, let alone how to program it. I just type =IRR(C4:G4) and voila!

With each update to Excel’s spreadsheet engine, the how gets faster and better, without the user having to lift a finger.

Most conventional languages are lower level, meaning that the programmer needs to formally define the computations that a formula or function needs to perform. Not just =(IRR…), not even just the full formula, but do this, then this, then this, then this, then this, then this. Depending on how these computations are implemented, there can be huge consequences for performance, accuracy, and stability - a large burden placed directly on the shoulders of the developer.

By operating at a very high level of abstraction, an Excel user is spared the headache of dealing with a lot of minutiae and incidental detail that is intimidating and frankly uninteresting to most people. Instead, Microsoft assigns an army of well-compensated developers to worry about the details, and the user just has to pick the right function to use.

Mental Model Inertia

Jakob Nielson, the iconic User Experience designer, defines a mental model as “what the user believes about the system at hand.” He stipulates that mental models are based on belief, not facts, and each user has their own mental model. Mental models are also susceptible to inertia: “There's great inertia in users' mental models: stuff that people know well tends to stick, even when it's not helpful. This alone is surely an argument for being conservative and not coming up with new interaction styles.”

Excel leverages a mental model that has been deeply ingrained in our culture for decades: a two dimensional grid using A1 notation. By assigning rows with numbers and columns with letters, a user can identify a single cell in a large 2D grid without confusion or ambiguity. By sticking to the same conceptual model that has been in use since at least 1979, people can understand how Excel arranges data without learning anything new.

The persistence of this grid model has led applications outside of Excel to adopt the same or at least a similar model, which in turn only reinforces the ubiquity of the mental model, making it a permanent fixture of our collective consciousness. Whether a 2D grid is optimal for many domains is hotly debated amongst engineers, but it’s almost irrelevant outside of technical circles given its inertia amongst the vast majority of potential users.

Reactive

One of the most magical aspects of Excel is that it is reactive. When you change an input to a formula in Excel, any output that depends on that input is automatically updated. Because Excel has been with us for so long, we take this property for granted. But most conventional programming languages are not like this: when an input is changed, each step that depends on that input needs to be deliberately re-run for the output to reflect the change.

By being reactive, Excel allows for a kind of playful interactivity. You can play with inputs and toggles to a workbook, simulating different hypothetical scenarios. For the insatiability curious, it can be downright addictive. But more than anything, reactivity makes it easy to get very fast feedback, and the faster a system provides feedback, the easier it is to understand how that system works. Excel is designed to optimize the speed at which its users develop skill at operating it.

Acquisition of skills requires a regular environment, an adequate opportunity to practice, and rapid and unequivocal feedback about the correctness of thoughts and actions.

Naturally Full Stack

Excel users are not only unwittingly programmers, they’re also unwittingly full stack programmers. An Excel workbook can be an entirely self-contained, end-to-end piece of software. One sheet might contain a database, another sheet might contain a set of formulas to transform the sheet with the database, and another sheet might be a user interface of sorts. The user interface sheet might offer the end user controls to manipulate inputs, while also presenting summary data and charts of the final outputs.

These familiar tabs are actually a front-end, back-end, and database, all in spreadsheet form.

Another piece of Excel magic is the ability to inspect and manually update the entries of a database contained in a sheet. This is just not the norm with most databases, which typically require developer skills and permissions of a database administrator to update.

By being naturally full stack, a single person can build a complex model in Excel without needing to rely on outside help. And for tasks that don’t lend themselves to easy division of a labor, this is an essential quality. Investment Bankers have long argued the reason that analysts and associates will spend 80 to 100 hours a week on financial models (in Excel, of course) is the lack of divisibility of their work; often only one person has all the needed information to build the model.

Excel combines the power of a programming language, the immediate usability of consumer software, and the skill progression of a video game with the flexibility to adapt to nearly infinite use cases. That’s a combination no other software offers, and it’s why Excel has been able to survive and thrive while millions of other applications have come and gone.

And it’s not going anywhere.

Excel has been around a long time, so we can expect Excel to be around for a long time.

That’s the Lindy Effect at work: the longer something lasts, the longer it can be expected to last. Something that has been around for a year is expected to be around for another year, but something that has been around for 100 years is expected to be around for another 100 years.

There are a couple of reasons for that:

- Quality. Cream rises to the top, and only the strong survive. Part of the Lindy Effect can just be explained by the fact that some things are higher-quality than others, that people recognize and appreciate quality, and that over time, higher-quality things tend to outlast lower-quality things. If you put Aristotle’s The Nicomachean Ethics on a permanent bookshelf and had people choose between it and some modern high kid’s philosophical ramblings in an ongoing tournament, generation after generation would recognize that Aristotle is better, and Aristotle’s work would survive.

- Network Effects. As people recognize something’s quality and as it lasts longer, they become more comfortable building on top of it, which increases the odds that the thing sticks around. That’s a form of network effect, specifically a Two-Sided Platform Network Effect. As Aristotle’s work persists, more philosophers build on top of it, and more philosophy professors build their curricula around it, which creates lock-in and makes it even more likely that his work survives for millennia hence.

Excel is Lindy software.

Introducing seamless reactivity to spreadsheets in a graphical interface created such a magical and intuitive experience that Excel was able to steal the lead from Lotus 1-2-3. As it’s evolved, new competitors have tried to steal market share, most seriously Google Sheets, but those doing serious analytical work in Excel’s core focus area wouldn’t dream of switching. Excel is too good at what it does. It won, and continues to win, on quality.

Meanwhile, Excel continues to build up serious network effects: many of the models that run businesses and markets are built on Excel, developers build plug-ins for Excel, banks and consulting firms train incoming classes of analysts on Excel, they practice Excel non-stop for years and get really good, and when they go on to start and run companies, they mandate the use of Excel. It’s also interoperable between firms -- you can send an Excel spreadsheet to any investment bank or hedge fund in the world and they’ll be able to open and work in it, which makes the lock-in stronger. As a test, pick your favorite hedge fund analyst, send them your model in Google Sheets, and see how seriously they take your idea.

John Updike has a quote that’s my favorite about New York: “The true New Yorker secretly believes that people living anywhere else have to be, in some sense, kidding.” That perfectly captures how Excel users feel about their favorite spreadsheet software:

Excel has stood the test of time by creating excellent software that turns anyone into a programmer, with a programmer’s snobby preference for their own language. Excel has been around for 36 years, so we should expect that it will be around for another 36.

That resiliency gives people the comfort to build on top of it for an ever-increasing amount of use cases. The combined daily efforts of 750 million users push Excel to, and beyond, its limits.

Nothing in life is without trade-offs, and Excel is no exception.

Excel’s flexibility and power is a double edged sword. Unlike many domain specific SaaS applications, Excel lets you do just about anything you want. Excel is not very opinionated software, nor is it constrained to prevent the user from doing things that might get them in trouble. In fact, Excel doesn’t even know the domain you’re working in. If you screw up a model of say, FIFO inventory tracking, no one even thinks to blame Excel - it’s assumed it’s your fault. If you use specialized FIFO inventory tracking software, it’s likely there are guardrails in place to prevent doing things that make no logical sense, at the cost of flexibility.

There is also a lack of data provenance in Excel. In scientific research, provenance refers to the origin of any data that is collected, along with a history of all changes or transformations to the original data. Provenance is essential for the reproducibility of research, otherwise a scientist cannot take the same raw data and get the same results. And provenance isn’t just an issue for academic scientists - it’s an essential quality for anyone doing data analysis. Unfortunately, Excel lets you do all kinds of complicated transformations of data, and yet lacks any sort of history of the sequence of those computations. The ability to copy and paste data into a tab that serves as a database means that any steps leading up to the pasted data are lost. What if the data that is pasted in is total gibberish? What if a sheet of numbers made sense at one point, but someone scrambled them? While transformations that live in code are documented in such a way to reproduce each change to your data, changes in a spreadsheet are not.

Excel is very hard to version and compare changes. While code is intimidating in many respects, the fact that it is saved as text makes it very easy to version and compare changes from one version to another. Most professional programmers use some form of version control and will share their code for feedback from other developers using tools like Github. An Excel workbook, on the other hand, isn’t very readable, at least not the way text is. A workbook might have multiple sheets, each with formulas referencing data on other sheets, making it impossible to grok what’s going on in any sort of ordered, sequential fashion. So even though Microsoft’s cloud suite allows some form of versioning today, it’s nowhere near as easy to reason about changes to an Excel file as it is to code.

While the 2D grid structure has a ton of mental model inertia going for it, it’s not always the right model, nor is it the only model with inertia. Long before computers, humans have organized information into hierarchical, tree-like structures. In fact, cognitive scientists have known for some time that the brain naturally processes information using hierarchical representations. Trying to implement a hierarchical, tree-like structure in a 2D grid is theoretically possible, but very unnatural and can quickly turn into a mess.

Roam Research has attracted a cult following by arguing the best way to structure notes and research is an associative graph, taking inspiration from Zettelkasten, a method for organizing information that dates all the way back to the 1500’s. So there are credible arguments that Excel’s ubiquity is leading us to cram information into a format that is less than ideal in many circumstances.

Until recently, Excel had one additional limitation: you couldn’t actually compute quite anything you could in other programming languages in Excel.

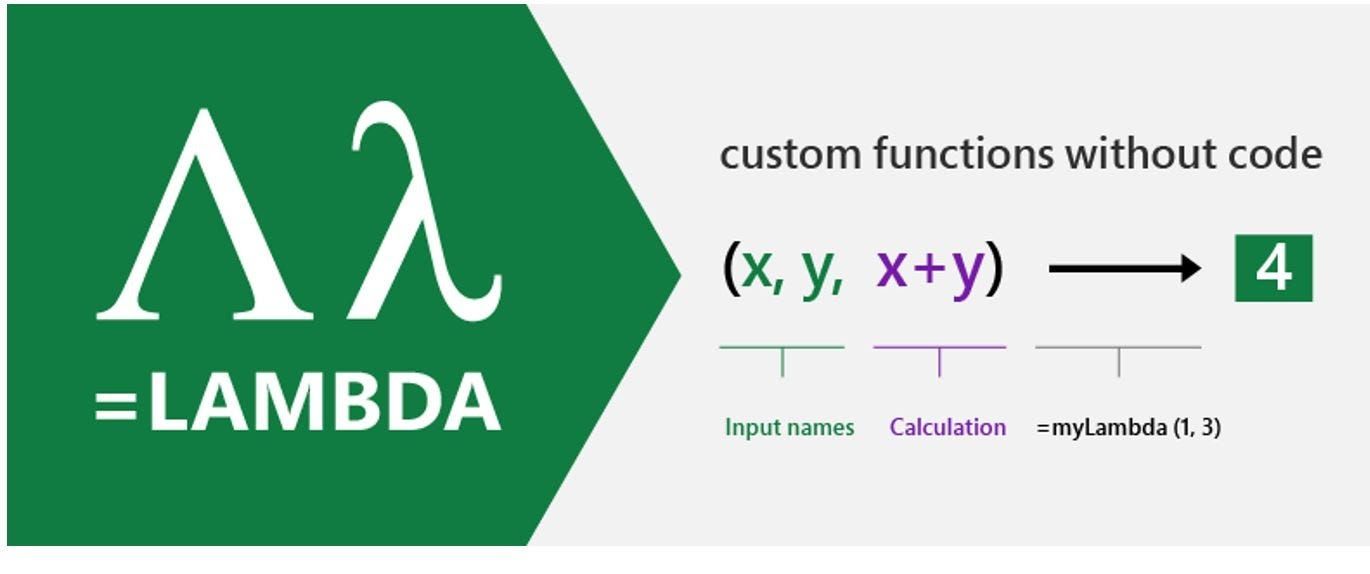

On February 9th of this year, Satya Nadella, Microsoft’s CEO, made a big announcement on Twitter: Excel is now Turing complete. In practical terms, this means Excel can compute anything you might crunch in Python, Javascript, or any other Turing complete language. At the root of this step change in flexibility and power is the introduction of LAMBDA - the ability for users to define reusable functions using Excel’s formula language. These LAMBDA-defined functions can call other LAMBDA-defined functions, allowing for recursion, transforming Excel into a “true” programming language.

While LAMBDA functions are arguably the biggest Excel release in a decade, they also sharpen the double edged sword that is Excel’s flexibility and power. A common refrain from experienced programmers is that just because you can implement something in a language, doesn’t mean you should. With LAMBDA, it’s rational to expect more and more complicated programs implemented in Excel, and some of these programs will turn into maintainability time bombs. LAMBDA increases power without addressing the limitations around versioning, reproducibility, provenance, and readability we talked about above.

Luckily, LAMBDA won’t only give Excel users more powers; it will give entrepreneurs more ideas for stable, single-use software based on the creative uses that Excel users come up with. Because Excel users have been setting the roadmap for B2B software for decades.

Excel’s influence reaches beyond the borders of the spreadsheet. It has a bigger impact on what software is built and how than it gets credit for. An enormous percentage of the successes in the last couple decades of B2B software have come from unbundling Excel, and we suspect that many of the next couple decades’ biggest winners will be Inspired by Excel.

The Unbundling of Excel

Excel serves a wider range of use cases well than any other software on the planet, but because of its limitations, there are some use cases that purpose-built software can handle best.

Excel’s flexibility lets businesses build all sorts of work flows and processes in the humble spreadsheet. They build databases, customer relationship management tools, calendars, to-do lists, project management dashboards, invoices, bug tracking, accounting tools, and more. The uses for Excel within a business are limited only by the users’ imaginations.

That creates an emergent product roadmap for the B2B software industry. Instead of needing to sit in a room and think up the future, a couple generations of observant entrepreneurs simply watched what people were cooking up in spreadsheets, sized the market, and built dedicated, less flexible tools for each specific use case.

In a 2017 blog post inspired by Andrew Parker’s 2010 The Spawn of Craigslist, Redpoint’s Tomasz Tunguz wrote about The Unbundling of Excel:

Excel has done a phenomenal job educating hundreds of millions of people about the power of software. Startups are taking advantage of this newly data-literate user base and carving out individual applications, replacing Excel with dedicated workflow that’s optimized for a particular function.

In May 2019, Ross Simmonds followed up on Tunguz’ post with These SaaS Companies Are Unbundling Excel -- Here’s Why It’s a Massive Opportunity.In it, he included a non-exhaustive graphic of some of the companies built to pick off pieces of Excel for specific verticals and functions.

There is nearly half a trillion dollars worth of market cap in that chart, with Salesforce leading the way at $193 billion, followed by multiple other unicorns including Asana, Tableau (acquired by Salesforce), and Workday. Salesforce is a good example of how it works: people were keeping track of their sales leads in Excel spreadsheets, which works but isn’t ideal, so Benioff and Co decided to build dedicated CRM software that does a lot of specific things a user can’t easily do in a spreadsheet.

CRM software is easy to grok because it’s essentially one database-looking thing to another, but practically any software that is built to handle data that isn’t super long text (which is unbundling Google Docs) is unbundling Excel. That’s almost every B2B software you know and love. Tunguz didn’t even try to include a graphic like Simmonds’ because the list of use cases Excel can handle pretty well is nearly infinite. We expect that more will emerge as software continues to eat the world.

But despite being nibbled at, Excel keeps getting stronger. Excel is Lindy. It’s not going anywhere.

That resiliency has inspired the next generation of entrepreneurs who are building some of the most interesting companies in the market with tools that don’t mimic specific Excel use cases, but the way it’s built and the flexibility it gives users to build for themselves.

Inspired by Excel

Inspired by Excel software products let users flexibly build on top of them the way that Excel users do. Instead of picking off specific use cases like Excel Unbundlers, they take inspiration from how Excel is built. They, like Excel, aim to create powerful general purpose, highly flexible software targeted at a broad audience, including non-technical users.

This HackerNews comment beautifully captures the difference between Unbundling of Excel (unitasker) and Inspired by Excel software:

If there is a core product design lesson to learn from Excel, it’s that combining usability with flexibility is both incredibly difficult and incredibly rewarding.

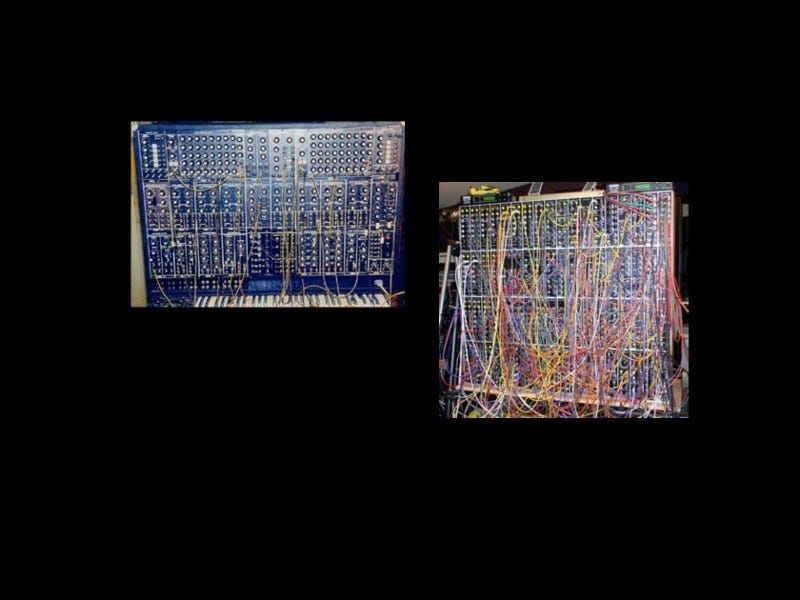

In an awe-inspiring talk, Rich Hickey, the creator of the Clojure programming language, draws a parallel between musical instruments and good software design. Hickey argues that musical instruments are quite limited for a reason - they are really good at producing what is actually a very limited range of sound. A saxophone, for example, can only play one note at time - unlike a piano or guitar. Expanding on the reason for the limitation of an instrument like a saxophone, Hickey explains: “Nobody wants to play a choose-a-phone...I'll take a step back and say maybe some people do want to play choose-a-phone, but no one, I bet, wants to compose for a choose-a-phone ensemble.”

Likewise, a design principle for developers is to make any one piece of software really good at one specific thing, deliberately constraining its capabilities to a specific domain. Excel is a truly remarkable exception to this rule - it is something of a choose-a-phone, and clearly hundreds of millions of people do want to compose for it.

Modular synthesizer, a figurative “choose-a-phone”

With the rise of No-Code and Low-Code products, a new generation of entrepreneurs is taking on the challenges of combining usability and flexibility for a non-technical audience, as Excel does. The space is attracting a ton of investment dollars, but it’s still viewed as something of a toy. That misses the point: no-code and low-code products put the creative power in the hands of the users, like Excel has, and create the conditions for an unpredictable explosion of new software usage.

Take Airtable, the no-code and low-code software on top of which users can build everything from structured databases to full websites, which was recently valued at $2.5 billion. Airtable is a particularly interesting example because it’s both Unbundling Excel -- it is better for structured databases than Excel but doesn’t even attempt to make it easy to do calculations -- and Inspired by Excel -- it’s increasingly becoming a platform on top of which users and companies are building solutions the Airtable team couldn’t have imagined. (It may be low-end disrupting Salesforce, too.)

Other no-code and low-code software like Figma, Roam, Webflow, Bubble, Zapier, and Notion are inspired by Excel’s approach without coming directly after its use cases. Even Looker and Amplitude, which aren’t generally grouped with the no-code/low-code movement, are more flexible than traditional analytics products and programmable by non-technical users. Shopify lets small businesses build full ecommerce stores by following templates or by mixing and matching thousands of Shopify-built and marketplace components.

Like Excel, these products are simple enough that non-technical people can use them, but flexible enough that users will create with them in ways that the product’s creators can’t anticipate.

Figma, ostensibly a no-code design tool that lets designers easily create and collaborate on anything from logos to full website mockups, is so flexible that in the beginning of the pandemic, a designer named Fiona created “WFH Town,” a shared virtual space in which anyone could build and hang out.

Bubble is a no-code website builder that lets non-programmers build production ready web apps, including robust back-ends and databases. It was literally inspired by Excel -- a builder can create a Bubble app by making a spreadsheet and linking it to Bubble.

Ben’s no stranger to this space. Composer, the startup he co-founded, is taking on the formidable task of trying to combine usability and flexibility, drawing on inspiration from Excel.

Composer allows the end-user to build custom, automated investment strategies, all without writing a line of code. Composer is flexible enough that it is intended to allow the user to create strategies that the founding team never anticipated. Before Composer, a strategy creator would need to be fluent in Python or a similar language to harness this degree of flexibility, severely limiting the number of people who could implement their ideas. At the same time, the team is constantly refining the usability of the product based on countless hours of customer research, leaning on the strengths of their product designer, Mikael, and cognitive scientist, Anja.

Zapier is a combinatorial multiplier that connects thousands of tools, like a series of codeless APIs, allowing for meta workflows across apps. With Zapier, any of the infinite things that an Excel user can create in a spreadsheet might trigger some action in Figma, Composer, or Weblow, or vice versa.

When the original Project Odyssey team set out to build Excel in 1985, they wanted to make it easy for users to perform calculations and create graphs. They could never have predicted the myriad ways over 750 million people would bend and expand the product. They just knew that the more flexible and usable they made it, the more possibilities they would create.

Similarly, this new batch of Inspired by Excel products will likely have unintended and magnificent consequences on the way that people create, build, calculate, and communicate for decades to come. Based simply on the exponential nature of these products, the impact of Inspired by Excel will dwarf the already massive impact of Unbundling Excel by orders of magnitude.

Excel has survived and thrived through the Spreadsheet Wars, the mobile revolution, and Unbundling of Excel. Excel is the bonsai tree of software: the more non-core use cases pruned off by unitasker products, the healthier it gets.

Now it’s entering a new generation of giving, one in which it’s not just giving off its useless appendages, but its very soul. Entrepreneurs are finally building based on the principles that have made Excel Lindy and allowed it to grow stronger and more loved for decades.

Those entrepreneurs can learn important lessons from Excel:

- Flexibility Matters. It’s impossible to know a priori everything a user will want to do. In order to evolve with users, product designers need to strike that delicate balance between usability and flexibility.

- Backward Compatibility with Existing Models. By translating ways that humans are used to thinking and behaving into software, product designers can make learning curves for complex products more gradual and natural.

- Product Architecture that gets better with more features. As more functionality and extensions are added to Excel, the better the product gets, because each new piece of functionality harmonizes with all the existing bits. This is as opposed to the many products that get worse with more features.

- Build for Your Passionate Core. Part of the reason Excel will never die is because there are so many passionate Excel practitioners. Inspired by Excel products should be flexible enough for non-target users to use (I love using Figma although I’m terrible at it) but endlessly challenging and rewarding for the target group.

As Inspired by Excel companies succeed and grow to multi-billion dollar valuations, there are only a handful of companies big enough to ingest them. We wouldn’t be surprised to see Microsoft begin to snatch up more companies in no-code, the space it ignited in 1985. If you squint, they’ve already started. Minecraft, which Microsoft acquired for $2.5 billion in 2014, is the closest thing to an Inspired by Excel product in all of gaming. People were confused by the logic even years after the acquisition, but no one understands the staying power of this kind of product better than Nadella’s crew.

But no matter how many new companies try to capture Excel’s magic, no matter how many succeed, and no matter how many Microsoft acquires, we promise, Excel will never die.

How did you like this week’s Not Boring? Your feedback helps me make this great.

Thanks for reading, and see you on Thursday,

Packy

Subscribe to Not Boring by Packy McCormick

Launched 3 years ago

Web3 and Startup Strategy, but not boring.